The Most Beautiful Box: Neutra’s Taylor House, Mies, and the “effect beyond four walls”

©barbaralamprecht2011 The text below is based on a talk I gave on Saturday June 11, 2011, for the Society of Architectural Historians, Southern California Chapter, at Richard Neutra’s Maurice and Marceil Taylor House, 1964, in Glendale, California. It was a beautiful day. The full-height glass walls on the north were thrown open so the 40-odd people could arrange themselves as they wanted, some standing a little removed on the sheltered terrace or under the oak tree off the living room, some draped on sofas and chairs, perched on the wide hearth of the floating brick fireplace, or sat on the floor. [1]

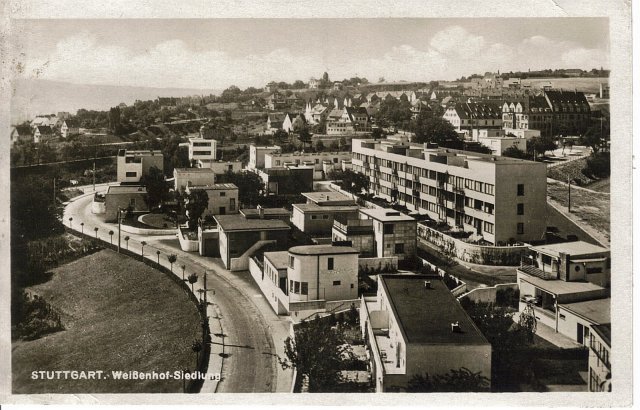

Breaking the box, thinking outside of the box, being boxed in: all are phrases that speak to the inflexibility of “the box.” In Modernist architecture, however, the right-angled box — at least dissembled and unskinned — was intended to be liberating, not confining. Some of Southern California’s finest “boxes” are a stone’s throw from where we’re sitting: in the Pasadena/Glendale area alone, there is the 1976 Art Center College of Design, by Craig Ellwood and Jim Tyler; Ellwood’s Don and Salley Kubly House, 1964; a host of excellent post-war projects by “USC School” architects such as Buff, Straub and Hensman, Whitney Smith, Wayne Williams, Thornton Ladd; and houses by Richard Neutra and his protégés Gregory Ain and Harwell Hamilton Harris. What distinguishes a Modernist box from the rest of boxes in architectural history is that the Modernist box is bigger than its actual footprint, as a Mies van der Rohe (1886 – 1969) anecdote illuminates: As the chief organizer of the 1927 experimental Weissenhof Siedlung housing complex in Stuttgart, Mies laid out the overall scheme, which included houses designed by great names such as Peter Behrens, Walter Gropius, Mies, Le Corbusier, Hans Poelzig, Max and Bruno Taut, Johannes Oud. Mies made a model of the hillside site plan: rows of little white flat-topped boxes, some bigger, some smaller, depending on whether they were single-family, multi-unit, or apartment blocks. Some were free-standing, some were detached, all staggered so that no box lined up with another above it or below it, and all were oriented parallel to the slope of the hill. The deliberately staggered configuration of volumes of different sizes, heights, and distances from one another collectively defined the little boxes as unified urban fabric, which a rigid alignment would not have achieved.

When a colleague on the organizing committee, a devout Modernist, challenged Mies’s apparently arbitrary scheme as not having enough Sachlichkeit,[2] Mies acidly retorted, “You seem to understand a plan only in the old sense, as so many separate building parcels. The model was meant to convey a general idea, not actual sizes. I believe it is necessary to strike … a new course. I believe that the new dwelling must have an effect beyond its four walls [my italics].”[3]That is, these boxes engaged the outdoors – the landscape, the sky – and other surrounding buildings — in new ways, and do so in ways that required elastic consideration of how much space there should be around a building. In effect, through the intentionally fluid location of his buildings on the site, Mies was asserting his individual will, acting against Sachlichkeit’s more formulaic and comforting retreat into the “functional.” Obviously buildings throughout history, such as free-standing Greek temples dramatically sited in a larger complex against a backdrop of rugged hills or contemporary structures ala Zaha Hadid, have always had a visual “effect beyond its four walls.” But these are not houses, let alone houses for the working or middle classes. Even Renaissance palazzos, villas for the rich with facades of masonry walls and “punched-in” windows, faced streets or squares with principal elevations. But the presence of glass, and a lot of it, complicates that effect. Glass dictated a far more calibrated relationship with their environment, but equally if not more importantly, the inhabitant also now has a much more complex relationship with whatever lay beyond the building footprint, which is what I’m exploring in this essay. The Modernists accomplished this larger Miesian effect in two ways: first, through transparency, by using ganged glass casement windows or with full-height glass walls, or both. Full-height windows elicit different psychological and physiological responses than casement windows, whose sills are about waist height; they also differ from highly placed clerestory height windows. Floor-to-ceiling glass assumes the full impact of a landscape or a view. The engagement with the outdoors is unmitigated, without shirking, no matter whether that provokes dread at full exposure or delight in expansiveness. And without a shield or window covering, this happens day and night.

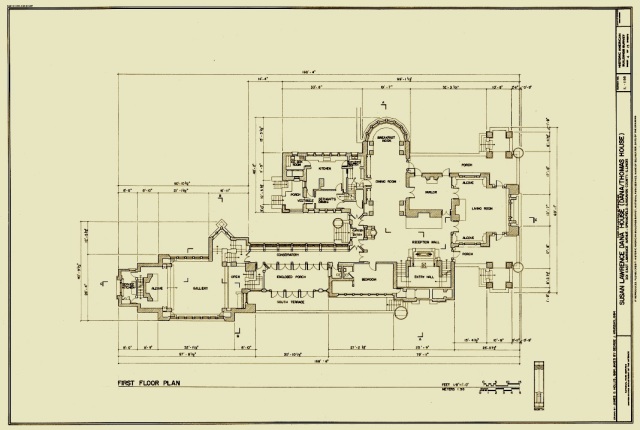

Dana-Thomas House, Springfield, Illinois, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1904. Source: U.S. Library of Congress.

The second thing Modernists did was to dissemble the box into volumes and then into discrete lines or planes. Initially, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959) started to break the box by stretching it in one dimension, almost making it seem ready to rip in tension. Soon he broke the box in terms of volumes that thrust out into the landscape, typically connected by narrow necks and bridges, beginning in the late 19th century with his houses in Springfield, Illinois, such as the Susan Lawrence Dana House, begun 1899, completed 1904. Certainly the Bauhaus in Dessau and the beautiful “Master” houses for faculty Lionel Feiniger, Walter Gropius, Wassily Kandinsky/Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, all designed by Walter Gropius in 1926, together are the collective celebrity of the idea of the white 20th century box dissembled into discreet volumes of glass and concrete. The “free plan” anchored Le Corbusier’s Five Points of Architecture, which he developed in the early 1920s. And surely one of the world’s most beautiful boxes is that of architect formidable Eileen Gray, whose E1027, Roquebrune near Monaco, with Jean Badovici, 1930, is bravely but brilliantly sited on the side of a precipice. And then there is Michael Hopkin’s exquisitely small-boned steel box of a house in Hampstead Heath, London, 1976:

Hopkins House, Hopkins Architects, Hampstead, 1976. Photo by Steve Cadman and used with permission, Flixkr

This idea of a connected group of volumes has retained its currency for architects for decades, such as the houses of the Case Study House architect and educator, the high-spirited Ralph Rapson.[4] He seemed unendingly curious about how to take apart a volume and put it back together, evident in his postwar and mid-century houses (I just returned from a trip to the Midwest, and stumbled on the famous University Grove, a group of 103 stellar Modern houses built for University of Minnesota faculty and staff on a leafy plot of land, including nine houses by Rapson and many more by the brilliant Close Associates, Winston Close and Elizabeth Scheu.[5])

We can see that dissembled series of volumes at the Community Facilities Planners Complex in South Pasadena, Smith and Williams, 1958. Instead of designing one monolithic structure housing offices, the architects created four intimate interlocking one- and two-story buildings interwoven with outdoor landscaped “rooms” by landscape Architects (Garrett) Eckbo, Dean, Austin and Williams:

Or we can see the idea of the dissembled volume, with far more opportunities to reach into the landscape and to avail the building of sunlight and air in the recently restored Zonnestraal Sanatorium [for tuberculosis], Jan Duiker, 1931, in Hilversum, Holland. I saw it in 2009 when the utterly abandoned buildings of glass and concrete were being restored, but Raymond Neutra, RJN’s son, photographed it quite recently in its newly restored glory:

On the other side of the ocean, especially in Germany, Austria and Holland, Wright’s 1911 watershed Wasmuth Portfolio of drawings, preceded by the March 1908 issue of Architectural Record, which published Wright drawings and photographs, was enormously influential in breaking the box, certainly for Rudolf M. Schindler (1887 – 1953), and Neutra. The other major influence was the de Stijl art movement founded in 1917 in Amsterdam. De Stijl, which comes from stile, or post, was based on sources including the ideas of Dutch mathematician M. H. J. Schoenmaekers (1875 – 1944); the architectural writings, drawings, and projects of Wright and Hendrik Berlage (1856 – 1934); and the religious philosophy of Theosophy. De Stijl held a similar understanding of “space” as did the Theosophists – that is, the “underlying and absolute All,” and the primary substance of Modern architecture. This was a view held by Schindler, who famously wrote “the most important building material of the 20thcentury is space itself”).

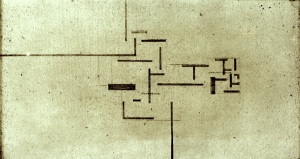

This primacy of space leads to the third component of Modernist boxes, which is the concept of the flowing, uninterrupted space, especially demonstrated by the paintings of Bauhaus masters Klee, Kandinsky, Theo van Doesburg, and Piet Mondrian. Van Doesburg and Mondrian’s abstractions of nature, music, and city life were rendered in color, shapes, and straight lines of different lengths that did not intersect, which underscored the idea of a space free to move, especially diagonally, and to be everywhere simultaneously, a posture assumed by Modern architecture. Two decades before Wright, the great 19th century architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White introduced flowing space in the firm’s “radical spatial reconception of the domestic interior, in their huge, sweeping Shingle Style houses typically sited on the shores of the American East Coast,” as critic Martin Filler has pointed out. This reconception, based on centuries-old Japanese vernacular architecture, was a “breathtaking expansiveness quite the opposite of typically compartmentalized Victorian residences, in which every room was a veritable room unto itself.”[6] (It should be added that the Victorians and turn-of-the-century arbiters of design mediated space very precisely to regulate social relationships, especially gender, status, and age. The McKim, Mead, and White work was therefore more radical in disorienting these often rigid spatial relationships.) The new, voluptuous sense of space in their work was in turn organized and disciplined by light wooden grilles above the openings.[7] And almost a half century before McKim, Mead and White, Catherine Beecher Stowe’s floor plan for the new American House, published in her Treatise on Domestic Economy, 1841, is riveting in opening up the ground floor to be altogether more flexible and functional, somewhat in the spirit of the Rietveld-Schröder House in Utrecht, Gerrit Rietveld, 1924, with its sliding and movable parts. However, this new, exhilarating sense of spaciousness in this early McKim, Mead and White work could not be completed, i.e. could not be realized, without the second, critical addition of “broad expanses of multipaned windows, often on two sides of the room, which in many cases gave onto the firm’s signature enveloping verandas” [just as the glass walls of the Taylor House opens to the terrace, as do thousands of walls in pedigreed and in millions of lesser status houses]. The fourth factor in facilitating the dissemblage of the box is the denial of a static frontal elevation; the denial of single-point perspective and the vanishing point and the rise of the diagonal. In a pinwheel plan, as seen in Mies’s Brick Country Villa, 1924, or Neutra’s Kaufmann Desert House, 1946, space immediately moves. It is no longer shepherded along in straight lines, halted or rigidly constrained. No longer static, space can move beyond hierarchy, diagonally or back and forth.

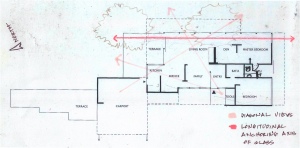

Another way to consider the emergence of the diagonal is the right angle, where two straight perpendicular lines converge. The hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is implied. With glass walls that meet at right angles (e.g., at the corners of walls) that diagonal “hypotenuse” view is realized. One can see this in the sweeping glass corners of Neutra’s early employer, architect Erich Mendelsohn, in his commercial work, especially the Berliner Tageblatt building (1923), which Neutra worked on. One can easily also see at least the desire for a diagonal view in the windows aligned with corners in Arts and Crafts architecture of the early 20thcentury. Obviously, we can see that idea of the implicit diagonal and free space in plan here in the Taylor House. But the free space is controlled. For example, the longitudinal axis on the east, private side of the house, is glassed at both ends as a strong linear anchor.

This ordered, traditional strategy provides a sweeping view through the entire length of the house and out of it, a very “Julius” moment.[8] Dancing against that axis are dynamic diagonal views and paths. In the language of environmental psychology, Neutra proffers “affordances,” or opportunities, to move axially or diagonally within this space, movement that in turn extends to the landscape and to the “natural” ornament of plantings, leaves, rough bark, clouds, which both animate the space and orient our visual and neural systems to scale and place. That, ultimately, is the point: physical and emotional well-being. If a building goes beyond its footprint in the precise way that Neutra designed, it allows the inhabitant, at a very primal level, to feel more secure, more connected to place, and assured of what is happening in the area beyond the walls. That ancient assurance, of the ability to apprise our environment, allows us to defend ourselves if necessary, but also provides us the affordance, the opportunity, to concentrate on other things that require more intellectual work, more neural activity.  Taylor House. Floor Plan w/ longitudinal and diagonal axes. Image barbara lamprecht

Taylor House. Floor Plan w/ longitudinal and diagonal axes. Image barbara lamprecht

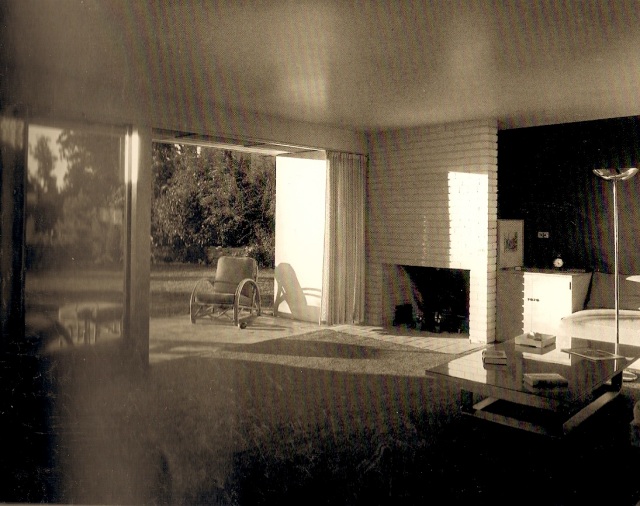

In this very rectilinear box, you can see specific trajectories for diagonal movement in the path from the carport south to the living area, a private path, and then to the outdoors; or from the front door west to the living area and then to the outdoors. In Neutra’s Ward House, 1939, the relationship between the fireplace, glass wall, and outdoor space speaks directly to the blurring of the boundary between indoors and outdoors. Neutra doesn’t locate the fireplace in the standard “hearth” location, centered on a wall, where the descendants of hairy humans gather round, well protected from nature. No, he does something that would be labeled crazy anywhere a real winter exists. Neutra’s gesture proclaims not only a benevolent climate — this is Southern California, could be East Africa, this fireplace announces — but also embraces the outdoors and the natural landscape as an equal partner in the act of dwelling, even at night. The brickwork is even painted white, just as the exterior stucco is, drawing the outdoors into the living room. Many other Neutra houses follow this pattern — including the Taylor House, in which the fireplace floats parallel to and a meter or so away from east window wall and the threatened Kronish House, 1955, in Beverly Hills:

The Ward House, Richard Neutra, Los Angeles, 1939. Photo by Julius Shulman. Print location: University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Special Collections. Julius Shulman images now owned by Getty Research Institute. Low-res scan source: Richard Neutra - Complete Works by Barbara Lamprecht.

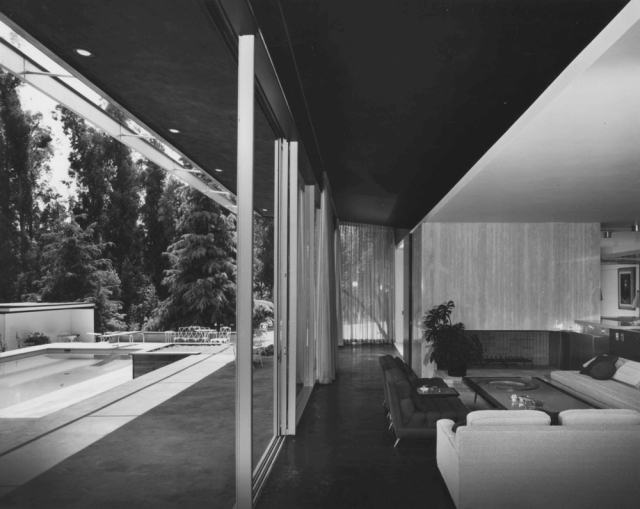

The Kronish House, Richard Neutra, Beverly Hills, 1955. Fireplace. View west. Photo by Julius Shulman and used courtesy of Dion Neutra.

For Neutra, the Taylor House is no less organic for its precise right-angles. That is, “organic” in the sense of the complex functional feedback and interaction of parts characteristic of living “organisms.” The building of inorganic materials was nonetheless holistic. The relationship between naturalscape and builtscape created a “thrilling dialectic,” in Neutra’s words. Most of us inhabit boxes, or decorated sheds, as architect/authors/urban planners Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour would say, some sheds and boxes more opaque than others.[9] If we think about inhabiting a box, they can be closed, in which case from inside we would have no sense of anything beyond the walls, unless we are inhabit a house with the aforementioned atrium. In the 19th century, not only did large plate glass not exist, but Nature was still too volatile to be trusted all the time, although theorist/architects such as Andrew Jackson Downing extolled the virtues of country living in his cottage designs. In lieu of woodland living, by and large out of reach for an increasingly industrialized society, the Victorians dragged the outdoors in, taming it with dried, dead bits of nature stuck in vases or covering their walls with patterns of the outdoors. Nature was other, and was only invited indoors when it behaved properly.[10] (Simultaneously, restorative garden cemeteries and public parks, newly available to the working and middle classes, became popular as appropriate venues for outdoor activities, a reaction to the Industrial Revolution that fouled nature and blackened the lungs of city dwellers and factory workers.) Nature was not the only thing a closed box could control. Privacy was another, especially if the world beyond the walls was increasingly incoherent. As the famous Viennese architect, iconoclast, and critic Adolf Loos declared, “The building should be dumb outside …” His early 20th century houses — his white boxes — are closed not because nature is the problem but because people are. His exterior walls embodied hostility and mistrust to a different “other,” e.g., the hypocrisies of the Hapsburg Empire and the Viennese public. Ironically, the Industrial Revolution also led to the perfection of manufacturing large-span plate glass. No longer a luxury, huge openings could frame views and permit abundant exposure to light, sun and nature. Like sanitoria, such access to the outdoors confounded dark dank spaces, bacteria, and killer airborne disease. Not long after my lecture I read a recent New York Review of Books article that startled me both in timing and in content. It noted that “organisms have skin, but their total environments do not. It is by no means clear how to delineate the effective environment of an organism.”[11] The author, geneticist Richard Lewontin, even included an old children’s song:

You gotta have skin. All you really need is skin. Skin’s the thing that if you’ve got it outside, It helps keep your insides in.… or not, if you’re a house with a lot of glass. Glass makes opaque skin a transparent membrane. A close friend of the owner of the Taylor House, the late sculptor/artist Gordon Matta Clark, would take a saw to create large holes in opaque boxes to expose us, if jaggedly, to the inner workings, the secrets opacity hides.) We don’t need a blowtorch or Sawzall with glass. It is a multivalent phenomenon. Looking into a glass house makes one a voyeur. To be inside such a house looking out has no such predatory connotation but rather is a wholesome exercise. Glass is the means or extending one’s self beyond the building envelope into nature, just as the building itself is having “an effect beyond its four walls.” In Modernism’s hands, glass afforded both access to nature and privacy, as the Taylor House demonstrates with its opaque street facade and its utter openness to nature for its inhabitants. The house is indeed a free-standing rectangular box of 1,350 square feet, but as a work of architecture it demonstrates how the act of perception can be altered to create feelings of expansion, or what the environmental psychologists Neutra followed so closely would call “prospect,” meaning looking out above your surroundings from a commanding position … afforded by glass walls. In contrast, the kitchen and the bedroom/dressing area, with their walls of warm mahogany, create the counterweight to prospect in the quality called “refuge,” or shelter, or what Gaston Bachelard called the cave. Both prospect and refuge are necessary to us. Neutra delivered a small space that feels expansive, not cramped, because it has an effect beyond its four walls. As he often said, his goal with small houses was to “stretch space” through another set of tools, Gestalt aesthetics, where dark and light paint were enlisted on behalf of his goal of prospect and refuge. But why a box? Why not curves, aren’t they more organic? Rectilinearity is as old as the Roman axis of cardo maximus and decumanus maxima, the north-south and east-west axis, respectively. Legend has it that Roman seers had to first examine the entrails of beasts in areas where a Roman city or military outpost was contemplated. This may sound superstitious but in fact is quite pragmatic. Bright, fat entrails meant food and water were nearby, portending a prosperous economy. And practically, standardized patterns for stone, wood, and metal are easier to use in design and in construction, and last longer than sun-dried bricks or mud. Neutra’s architecture is to a degree standardized. It acknowledged and acquiesced to Western building traditions, but his appreciation for the straight line and right angle (which in fact was sometimes tempered by a radiused curve, seen in some early interiors) goes deeper than that. He was always searching for reasons for why things should be a certain way; his architecture always reveals itself as a profoundly intuitive art that was grounded in science. The apparently quite banal Los Angeles County Hall of Records, designed by Neutra and his erstwhile partner Robert Alexander and completed in 1961, comes to mind. A T-shaped building anchoring the north end of the city’s civic plaza, the south-facing stem of the T is a massive closed box devoted to the storage of paper records, today a consummate symbol of an outdated paradigm. But for the rest of the T, occupied by hundreds of civil servants, planners, clerks, and policy makers, among other consultants Neutra hired a “kinetic ophthalmologist” to assist the design team in understanding how tracking the sunlight and changes in daylight over the day could ultimately be correlated to worker productivity and well-being. (If I hadn’t read the phrase and the consultant’s name, I wouldn’t have believed there was such a profession, but Neutra managed to find one – or upgrade a regular opthamologist — to sway politicians.) Calibrated exposure to the outdoors was necessary for the building to act organically and to promote human health, emotional and/or physical. “Rectangularity, the intersection of the plumb and the level, is a biological fact,” Neutra said. “We have a wonderfully acute sense for it in the vestibulum of our inner ear where resides our precious sense of equilibrium. The plumb shows us precisely the direction of the pull of gravity and its relation to the water level of the horizon with which it, and the vertical, intersect in a crisp sharp emotionally satisfying right angle. Piet Mondrian was no false saint. A sense for it [rectilinearity] has truly been grown into us by creation.” Thus, Neutra makes no apologies for the straight line, which he often extended into the natural landscape along with his famous “spider legs” to connect landscape to building. Mies didn’t apologize either, and one recalls that he appropriated the thinking of the great 19th century German architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who considered architecture as an abstraction of nature. In the Taylor House, the floor-to-ceiling wood storage cabinets and closets are largely massed in the core of the building, allowing, even in comparison to many of his houses, many expanses of floor to ceiling glass. And I don’t think in any other house will you feel as liberated without abandoning the feeling of shelter if you want or need it. There are very few doors to regulate privacy, a sensual editing decision, at first glance, for this older couple whose children were grown and gone. But privacy is nonetheless there, rendered spatially rather than through the use of doors. The house also faces, primarily, east-west, usually an architectural no-no. But that brings us to the trees, and to the artistic way that Neutra sited this building: I can’t imagine a more richly textured dialectic, between the angles and curves and kinks of the oak trees, that is, the squirrels’ thoroughfare, and the rhythm of the square silver-painted posts and transparent glass? Think about it: in the VDL Research House II, Neutra objected to his son Dion’s inclusion of the open-tread diagonal staircase from the upper floor to the rooftop penthouse. Here in the Taylor House, the diagonals are present but in their natural form, as part of the tree, not part of the house. The only place that is curved is near the front door, where nature slips under the glass as a small, curved pond (once water, now Japanese river stones) that compresses a Roberto Burle Marx garden into a slight and economical gesture ….

The description of the Taylor House from Richard Neutra – Complete Works (Taschen 2000):

The narrow rectangle lies on an equally narrow strip of a site sits on “a really unapproachable piece of land at the end of a dead-end street” Neutra wrote. Surrounded by oaks, the small house is spacious, highly organized, easy-going. No attitude. What looks to be a judicious use of lines and planes unfolds into a complex integration of events that knit the house together seamlessly and created the context for dwelling. The Taylors’ children were grown. This was the couple’s pied-a-terre. In the little house, all the standard Neutra moves are here but compressed, as though the neatly rendered small stroke works just as well as the grand gesture. In plan, the private path starts from the carport to the northwest, leads to the kitchen and opens out to either an outdoor terrace on the northeast, to the dining/sitting area, or through an opening to the “book” end of the living room. It continues flowing diagonally past this central space with its east floor-to-ceiling glass wall. The transition to the master suite begins with the fireplace. Here the path forks, either to the smaller bedroom and bath on the southwest or the master bedroom at the southeast corner. In classic Neutra language, the over-scaled fireplace is pulled away from the window wall and placed perpendicular to it. By cantilevering it and enlarging the hearth, Neutra conferred its sense of weightlessness; he added texture by using both Roman and common red brick around a plaster firebox. Beyond the fireplace, the core of bathrooms, floor-to-ceiling cabinetry and the dressing area creates privacy for the master suite. There are few doors in the house, supplanted by other full-height mahogany built-in cabinetry throughout the entire house. Other small gestures occur at the front door (Neutra typically separated public and private access, which usually connected to the kitchen) where a simple dark burlap panel compresses space and prolongs the delay in seeing the entire living room’s wall of glass and, typically, a squirrel or two sliding and darting along the big oak branches beyond. The dwelling stands above fairly dense suburbia, and yet once inside, privacy and a stunning up-close panorama of the oaks as well as the San Fernando Valley confer instant serenity. The master bath adds a special feature, making it feel like a rustic Japanese bath. Here one glass wall faces a sunken bathtub. One could easily rub noses with a coyote or deer drifting who inhabit the low Los Angeles mountains all around.

Glass is the membrane separating nature alert but at ease beyond the glass, observing nature alert but at ease inside the glass. View east. Photo by John Solomon.

| [9] See Learning from Las Vegas, Revised Edition: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour. Boston: MIT Press, 1977. |

I believe the photo at the end of this wonderful piece with the deer lounging next to the window of the Taylor House is by John Solomon. It’d be nice to credit him. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hello Julie, thank you for the correction; I thought someone else had taken this but I think you are right.

LikeLike

Thank you Barbara, Wonderful piece you wrote. I especially loved the comparison to the great painters.

LikeLike

Hi Renee,

Hey, thank you very much! See you in August 🙂

LikeLike