What Set Him Apart: The Books on Neutra’s Shelves

Modernist architect Richard Neutra (1892 – 1970) is renowned for his sleek, taut form-making. His ubiquitous trademarks include full-height glass walls, flat roofs, silver paint, white walls, bands of identical fenestration, crimped metal fascias, and broad overhangs. Above all, there is his famous “spider leg,” where a long beam stretches out beyond the building envelope, eludes its grasp, to meet a freestanding column, which catches it. This “structural tentacle,” as he called it, is not just the building actively reaching out to engage a passive earth, but an umbilical cord balanced among equals.

His compositions unmistakably reflect artistic genius and the sensibility of a true believer in the power of Modernism, sure, but that is only half the story. His trademark features reflect his belief that when architecture is wedded to a range of sciences, including anthropology, evolutionary biology, environmental psychology, cognitive science, and Gestalt aesthetics, buildings could be ameliorative, therapeutic, and enrich human perception. Only by understanding the subtle connections among universal genetic propensities; the apparati of all the senses, and individual behaviors and desires, could one design an “architecture of applied medicine,” as he put it, urgently needed in an increasingly incoherent world.

He elaborated on his theory in his books including Survival Through Design, 1954. His other books include Nature Near, 1989 (a collection of essays compiled by his widow, Dione) and Building and the World of the Senses, 1980 (written with his architect son, Dion.)

Neutra defined his approach to design as ‘biorealism: “bio” from the Greek word bios, meaning life, and “realism” because architecture had to take its cue from how humans really behave, not how they should behave. Biorealism addressed the universal and the general, that is, we are all the same but at the same time none of us are the same. Neither was biorealism dryly “functional.” Architecture also had to be supple enough to embrace the “honeymoon moments” in life. It was sensual as well as intellectual. His tectonic “dynamic symmetry,” a balanced asymmetry of line, plane, and volume, was met and matched by the balance between the universal and the specific, the human and the generic.

His lifelong immersion in these sciences led him to a definition of nature that set him apart from his peers in the pantheon of great 20th century architects. Nature was not “other” than humanity. Rather, humans were part of the spectrum of nature. Therefore, a building didn’t have to look Frank-Lloyd-Wright-“organic” to be organic. Thus, even though Neutra’s architecture is often portrayed as a “machine in the garden” (to coin the title of Leo Marx’s 1964 book on the American dilemma of advancing technology while getting away from it all), there’s another way to look at it. For Neutra, the real machine in the garden is the human, whose daily experience could be calibrated by her environment, fine tuned to fit her precise, a glove. To Neutra, an architecture that is lived, not only looked at, was “red-blooded in tooth and claw” even if it was fabricated by machines.

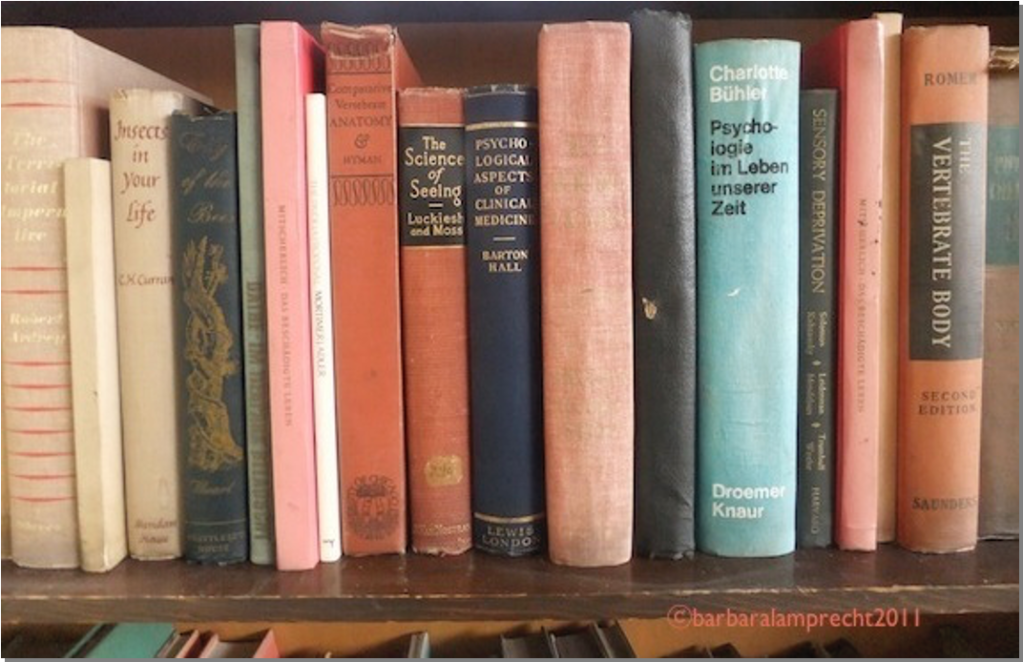

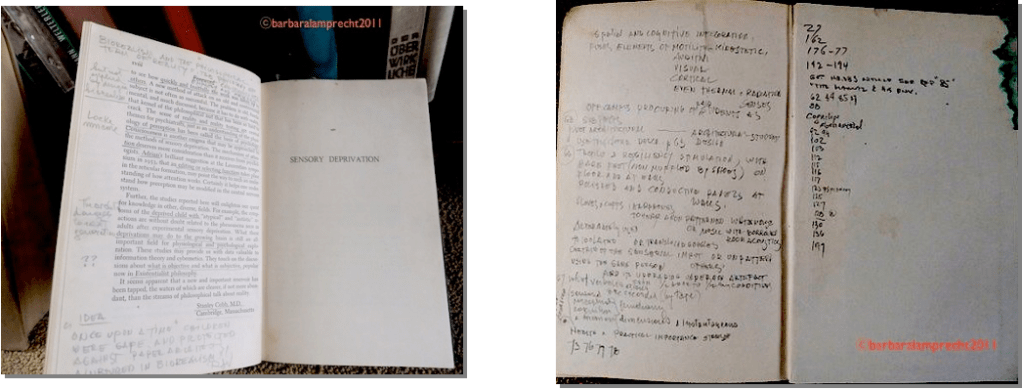

Since he professed to anchor rationales for the architecture he designed in these sciences, I looked for books on his shelves that bore witness to that conviction. In the late 1980s I documented the books in the family home, named VDL Research II, overlooking Silver Lake in Los Angeles. His books speak to a deep cultural literacy. (I also found anomalies such as the handsome, colored-tinted volume containing renderings of Reich Chancellery. The infamous Albert Speer had signed the large volume and given it to Neutra. He visited the Nazi architect after his stint in Spandau Prison to ask him to explain how, how, he could have worked for the Third Reich.) However, the books I now sought anew were for my research for my dissertation at the University of Liverpool. These are located on the low shelves below the windows on the second floor, the family’s airy living and dining space. It’s likely that many more books were destroyed in the March 1963 fire that destroyed the first home, VDL Research House I. But I did find some survivors.

Some of the titles, mostly dating from the 1930s to the 1960s, include Insects in Your Life by Charles Howard Curran, 1951; The Territorial Imperative: A Personal Inquiry into the Animal Origins of Property and Nations and African Genesis, by Robert Ardrey, 1966 and 1968, respectively; Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy, by Libbie Hyman, 1922; The Science of Seeing, by Matthew Luckeish with Frank K. Moss, 1937; Psychological Aspects of Clinical Medicine, by Stephen Barton Hall, 1949; Psychologie im Leben unserer Zeit [Psychology in the Life of our Time] by Charlotte Bühler, 1968; Experimental Social Psychology; [author tk] The Prenatal Origin of Behavior, by Davenport Hooker, 1952; Science and Man’s Behavior: The Contribution of Phylobiology, by Trigant Burrow, 1953; and The Vertebrate Body, by Alfred Romer, 1949.

Today, of course, environmental psychology research fuels a small avalanche of people designing virtually anything where any the senses are involved, smell, touch, sound, sight, balance … from hospitals for Alzheimer’s patients to exquisitely branded retail spaces, where the diameters of a tables will help determine how long a coffee drinker lingers or the lighting above a jewelry counters turns indecision into yes! As Neutra rather outrageously claimed and savvy health insurance companies now realize:

“The resolve of hospital patients] to get well can depend on how cheerful, warm and reassuring those settings are …”[1]

or:

“In a courtroom, justice is conditioned by changes in the air characteristics of the room and from soporiferous butynic acid and body odors.”[2]

Biophilia, the title of naturalist E.O. Wilson’s well-known 1984 book, champions similar and now quite popular ideas, but biorealism is known only to cognoscenti and many times not even to those who love Neutra. It is time to realign that absence, and Neutra’s books are the perfect vehicle for demonstrating an approach founded on rationalism and informed by an intuition masterful in proportion and scale. Science didn’t “drive” the buildings Neutra designed. Rather, they demonstrate how science could inform design to create environments that exulted in the connection between human nature and the Nature of the natural world.

[1] Nature Near, p. 5.

[2] Unpublished paper dated 14 February 1969, “Sozialpsycholgie und Architektur”. Translated by Alphonz Lamprecht. Neutra Archives, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.