The Obsolescence of Optimism? Neutra and Alexander’s U.S. Embassy, Karachi, Pakistan

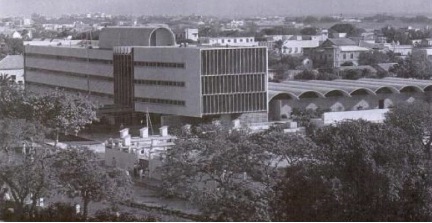

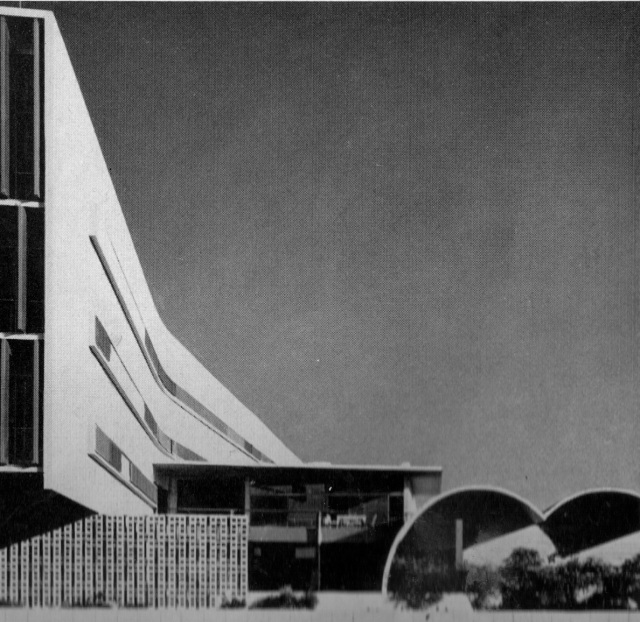

- View of the former U.S. Embassy, Karachi, Pakistan. Photo by Lucien Hervé. Source: scanned from Richard Neutra 1961 – 1966, Buildings and Projects, Thames and Hudson. Camera facing southwest.

Dedicated to the Honorable John Christopher Stevens, Ambassador of the United States of America:

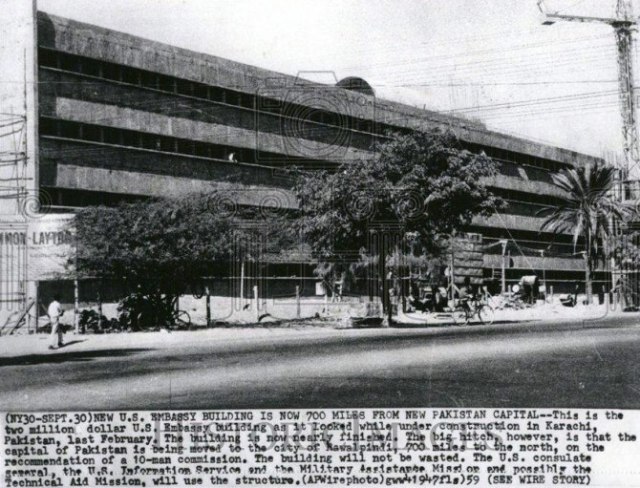

What happens to an outmoded mid-century American embassy? Given the consistently tortured relationship between Pakistan and the U.S., the names of the cities, Karachi and Islamabad, are quite familiar. But it wasn’t until the former U.S. Embassy in Karachi was threatened — by demolition, not by assault — that I actually looked up the cities because it was designed by famous Modernist Richard Neutra and his partner Robert Alexander. Where these cities were geographically, one the current and the other the old capitol, was, eerily, linked to the fate of the Karachi complex. Even as it is stands today, silent and abandoned, the sleek complex still effortlessly exudes the optimism of postwar America. In fact, the embassy was doubly endowed with optimism because its primary design architect, Richard Neutra, was himself the most earnestly optimistic and least ironic of all the Modernist greats. Here, in Karachi, he applied his full repertoire of faith in the future here … after almost losing the commission because of suspicions that the German-speaking, Viennese-born Neutra wasn’t a loyal American.

However, it is irony, not optimism, that frames the life of the former embassy. Sparked by a 1958 attack on a South American embassy, the U.S. was already issuing directives on strengthening embassies just as the Karachi facility, designed to pre-1958 security standards, neared completion. Sure, it had plenty of individual secure features, but its overall democratic gestalt of decentralized buildings, inviting gardens, and a proud glass public entry proved too difficult to “harden.” Worse, the capitol moved from Karachi to Islamabad in 1961, jerking the political raison d’etre rug out from the complex just as it was completed.

Given its prestigious location in downtown Karachi and with no formal protection as a historic resource, the former embassy is a viable candidate for demolition … or reuse: in late 2012, the application for Heritage listing presented by a group of Pakistani architects and community leaders won approval, thus preventing demolition or major exterior alterations. Here is the back story:

In 1961, the Berlin Wall rose and the U.S.-backed Bay of Pigs in Cuba failed. That same year Pakistan moved its capital from Karachi, the old colonial port city on the lip of the Arabian Sea, to a raw new city under construction 700 miles to the north. The shift pushed the capital deep into Asia’s belly. Land-locked (and thus less vulnerable from attacks from the sea), the new capital, Islamabad, occupies the edge of a high plateau. It is the antithesis of sea-level Karachi, at the mouth of the River Indus and due east of the Gulf of Oman. This transportation nexus of rail, sea, and river made perfect sense to the British, who ruled from the 1840s to 1947, when Pakistan became independent. As with India, the Brits infused Karachi with the essence of Raj, with beautiful parks and the 19th century classical and Victorian architecture is so associated with civic Raj sensibilities. Raj held such cultural hegemony that the notorious explorer, Richard Burton – same name, different man – could spurn one architectural proposal for a new and exclusive men’s club downtown, the Sind Club, saying, “the Veneto-Gothic [a decidedly bombastic Victorian style of architecture used for the nearby Frere Hall, 1865], so fit for Venice, so unfit for Karachi …” Burton and his British peers, not the natives, decided what suited the city.

The Sind Club, 1890s. Photographer unknown. Copyright © British Library Foundation. Source: Eurocana.

So, a classier Italianate style was used for the Sind, completed in 1871, but the club did make sure to maintain the de rigueur sign, “Natives and dogs not allowed.” The sign stayed in place for 76 years until August 14, 1947, a day after the first Governor-General of Pakistan took his oath. The capital’s move north 14 years later signaled a a new self-defined future for the new nation, rejecting Karachi’s colonial roots and its fragile location by the sea. Despite its loss of political status, Karachi remains the nation’s economic powerhouse.

That same year, 1961, just as Pakistan’s government was heading north, the U.S. dedicated its new embassy complex in downtown Karachi. It was a prestigious site on Abdullah Haroon Road,[2]facing east and the old trees, lawns, and verdant greenery surrounding Frere Hall and the Sind Club. Designed by Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander, the embassy complex was regraded to consulate status in 1966, when the Ambassador and embassy staff decamped to Islamabad.

In 1999, the one barrier, a steel picket fence in front of the embassy–the slenderness of the fence itself a signal of optimism–was encased in concrete. The formal entrance driveway was also sealed off so that the sole remaining entry was from the service entry, Brunton Road to the south. The complex was “hardened” after a series of attacks began after 2000, but the intensity and frequency of the attacks continued to increase. After a 2002 bombing and at a cost of $10 million, the consulate staff moved from the long, four-story main building to the [3] one-story warehouse behind it to the west; in any case the low-slung warehouse was already more difficult to access from the street given its protection on the east by the big main building. Although part of the original design, the warehouse was clearly déclassé, not appropriate to consulate duties and constant public interaction, obviously difficult to adapt, and in any case still too vulnerable. In the face of such troubles, the complex’s sense of optimistic cool, suddenly seemed naïve, outmoded, dysfunctional, gauche. In 2006, the Office of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO) acquired a new site for a new consulate office and housing complex, now completed, commissioned, and occupied.[4] The Consulate moved out of the property completely in January 2011 just as Frere Hall was reopened. It closed after the 2002 attack, which had killed both Pakistani and American diplomatic staff.

Not only was complex politically obsolete as an embassy in 1961. Even at that early date it was already on the road to being physically obsolete as well. In 1959, security at all embassies suddenly became more urgent when 10,000 Bolivians stoned the American embassy in La Paz. “Security officially entered into the embassy building consciousness in 1964,” with calls for less glass, more perimeter fencing, and better protection of openings.”[5]

Neutra and Alexander’s effort was one of many embassy commissions, all reflecting the decision to rapidly populate the globe with a dignified but powerful—but not too obviously powerful—American presence after its World War II triumph and emergence as the world power. The State Department was quite aware of the acclaim of Modernism in buildings such as Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building, 1958, in New York. For a while, the Department managed to overcome the relatively mild Congressional grousing about the style, and became the preferred vehicle for exporting American values in concrete, glass and steel. Around 1950, the Office of Foreign Building Operations (FBO, the precursor to the OBO) commissioned internationally distinguished architects such as Walter Gropius/TAC; Jose Luis Sert; Skidmore, Owings & Merrill; Edward Durrell Stone, virtually all Modernists in style and conviction, to convey this new American identity. Crisp, suave Modernism, almost invariably featuring plenty of glass, replaced the government’s sober “starved” classicism of the 1920s and ‘30s. I was astounded to learn that architect Ralph Rapson was one of the first architects to be chosen: astounded because the now-venerable Rapson, later a faculty member of MIT before becoming the University of Minnesota Dean of Architecture, was one of the most creative and playful of all the designers in the elite Case Study House program, a postwar program of experimental Modern residential architecture.[6]

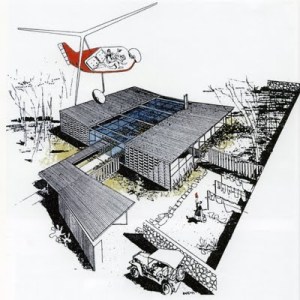

Ralph Rapson’s famous, or infamous, unbuilt but highly influential “Greenbelt” project, 1945. While iconic because of the housewife in curlers at her laundry, waving gaily to her helicoptering husband, Man-in-the-Gray-Suit meets George Jetson, Greenbelt is a thoughtful illumination of the critical role nature should play in domestic environments in a project that internalizes landscape.

In 1951 he was charged with four European embassies, for which there were “virtually no programs, no set budgets, no precedents … and little overall supervision” – perfect petri conditions for Rapson and his partner, John van der Meulen. Needless to say, such freedom didn’t last long.

Postwar and Mid-Century Embassies The “little overall supervision” that Rapson and van der Meulen had enjoyed soon became a thicket of requirements throughout the 1950s. The Pakistan embassy followed the now standard FBO design brief for embassies/consulates that was simultaneously, maddeningly, a daunting task: The new outposts were to be legibly American and convey strength, yet not be too assertive or flamboyant; the design should be Modern, excellent, and worthy of peer acclaim, but not too radical, befitting a dignified American outpost; it should be physically secure and robust, but not too costly let it alarm the American tax payer and thus Congress.[8] Programmatically, the embassies were “much like the headquarters for a small corporation,” including extensive, flexible office space for consular needs; staff and executive/ambassadorial offices; special facilities open to the public on occasion or for related government agencies such as the United States Information Agency (USIA) and the United States Information Service (USIS).[9] Other requirements specific to Pakistan included a controlled service yard and parking area; a substantial water storage tank, an electrical generator and “extensive warehouses to harbor American Governmental employees from neighboring countries and possibly their families and belongings in case of emergency.”[10] More subtle aspects of the FBO brief encouraged a “sympathetic, regional expression of our own architectural thinking” in designs that to some degree acknowledged the host country’s architectural traditions, climate, and culture.[11] (For Neutra, who had long argued that a building could readily be Modern yet synthesize just such a sympathetic response, the directive was no less than obvious.) Such a delicate balancing act is still very much a charge in embassy design half a century later. In a May 2011 article by OBO Acting Director Adam Namm, published in Ambassadors Review, the directives for the new “Design Excellence Program” for the design and construction of diplomatic facilities are strikingly familiar:

“Design Excellence will deliver facilities that represent the best of American architecture, engineering, technology, art, and culture while providing the best long-term value to the American taxpayer. Designs will be more responsive to their local context, to include the site, its surroundings, and the local culture and climate … Buildings will make greater use of contextually appropriate and durable materials. We must have diplomatic facilities that are respected but also respectful of their environments.”But this unchanging directive has been made far more strenuous by the contemporary repertoire of security concerns along with the need to incorporate sustainability and “green” building strategies, both predictable even if necessary and laudable. What’s interesting, however, is the new role that landscape architecture will play:

“The grounds and landscaping will be as important as the architecture, and together are to be conceived as an integrated whole. The grounds will be viewed as functional and representational space, and will be sustainable, and include indigenous plantings and incorporate existing site resources, such as mature trees …

The Architects

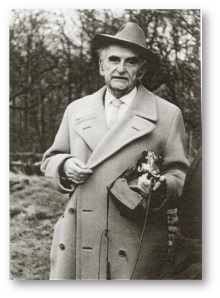

Neutra 1960s, Rang House, Koenigstein, Germany. Photographer unknown, perhaps Martin or Christina Rang, whom I visited in 2010.

Richard Neutra

In the pantheon of iconic 20th century Modernists, Richard Joseph Neutra is acknowledged for his exquisitely sensitive approach to the site. Mystery and Realities of the Site (1951), Bauen und die Sinneswelt (Building and the World of the Senses) 1980,[12] Plant Water Stone Light, 1974[13] and virtually every bit of the rest of his writings, legendary in their volume, are ceaseless calls to weave the natural world into architecture. For Neutra, this was an adventure linking curiosity about his human client with a close investigation into a site’s genius loci: equally legendary, for example, was Neutra tramping a prospective site, bemused but impressed clients trailing behind, struggling to keep up – in one instance, through the mud and wet undergrowth one moonlit night as Neutra traversed gullies and ravines outside of Washington, D.C.[14] As he told them, architecture was equally experienced at night as well as the day, so he scheduled his flight from Los Angeles to coincide with the full moon. (Of course. Every architect does that.)

Along with his fellow Viennese architect Rudolf M. Schindler, Neutra arrived in Southern California in the 1920s. Both were drawn to America through the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio of drawings destroyed “the box,” that is, conventional contained volumes. The Portfolio electrified European architectural circles, including the young Schindler and Neutra. By the 1920s, their distinctive approaches, completely different from one another in both philosophy and execution yet both devoted to a new vision, recharged Southern California architecture, contentedly devoted to Craftsman and Spanish/Mediterranean paradigms. Today Los Angeles boasts the finest collection of single-family Modern houses in the world, largely fostered by the pioneering lessons of Wright, Neutra, and Schindler and later their followers and proteges including John Lautner, Harwell Hamilton Harris, and Gregory Ain.[15]

Neutra’s Philosophy: Biorealism

Neutra’s Lovell Health House, 1929, Los Angeles, and the Kaufmann Desert House, 1947, Palm Springs, propelled him to worldwide fame along with Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius. Neutra is unique, however, in seeing nascent 20th century industrial technologies such as large plate glass, steel, Masonite, Formica, plastics, and waterproof plywood not as ends in themselves nor as enemies to Nature. Rather, he understood them as vehicles for apprehending his ultimate goal, an environment melding human construction and the natural world. Along with unearthing a site’s secrets and potential, his other primary objective was to understand human biology, cultural anthropology, and cognitive systems so that he could serve his client better.

While Neutra is renowned for his houses, asymmetrical assemblies of lines and planes that coolly slide out into the landscape, his work in schools is even more radical because it reconceived education along with the building.

Neutra’s theoretical “Ring School,” 1925, decentralized education and brought learning down to the ground plane. Each classroom opened out to the landscape to double available space, but also opened to the center courtyard and play area for corporate gatherings. The revolutionary scheme was realized at the R.J. Neutra School at the Naval Air Station Lemoore, California. It was completed in 1961, the same year the Embassy was completed.

He took the model of the four or five story monolithic masonry schoolhouse and brought it down to ground level. He spread classrooms and libraries and auditoriums into the landscape so that children could avail themselves of nature through glass sliding doors and broad overhangs to shade a classroom or provide protection from the rain. Dynamic, bombastic, brilliant, emotionally needy, deeply thoughtful, his writings reflect his passion for science blended by a voracious curiosity about humanity.

Robert Alexander

Educated at Cornell University, Robert Evans Alexander was a distinguished architect and urban planner whose achievements included the co-design of Baldwin Hills Village, an award-winning master plan development for over 600 units built in 1945 in Los Angeles. As Neutra biographer Thomas S. Hines has pointed out, Alexander’s savvy with politicians and urban issues along with his expertise in large-scale projects make him a natural choice for Neutra. Neutra and Alexander designed college campuses, churches, military housing, commercial buildings; one of their most famous projects is the Lincoln Museum and Visitors Center, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 1961.[16] The partnership began in the early 1950s with the ill-fated master plan development called Elysian Park Heights. If built, the project would have uprooted the longstanding community, primarily Hispanic, living in the hills above downtown Los Angeles, a place known as Chavez Ravine. In any case, the 230-acre public housing project was been denounced as a “socialist plot,” terminated. The land is now a baseball stadium. Though the very public failure hurt the architects, the project had enough legs to bite the architects a second time when the Embassy project appeared.

By the time the commission for the Embassy arose, Neutra was world-famous, a globe trotter of the first rank, used to swimming easily in cultures that might have been foreign to others but were quite native to him. The reflecting pools and water channels, for example, that skillfully weave the Karachi embassy together in a subtle but critical way, could be interpreted as solely honoring and including Muslim garden traditions into the complex per the State Department brief relating to local traditions and culture. (Yes and no. I believe Neutra would have done this anyway.)

The budgeted cost was $1,000,000, comparable with other embassies. Much of the expenditure was not from an outlay of American dollars but foreign postwar credits owed to the U.S, allowing the U.S. Treasury to obtain equipment, materials, and labor in exchange for a particular country’s debts.[17] To Robert Alexander’s consternation, foreign currency (in this case, the fluctuating rupee, far more volatile than the dollar) would also be used to pay architectural fees for American firms working abroad. His letter of protest to the State Department apparently almost cost the partnership the job when the Department of State curtly returned its contract to them unsigned, stating basically that that was the deal, take it or leave it. They were, presumably, off the job. Herculean efforts by Neutra followed that were savvy, manipulative, and a little hysterical. He frantically contacted any number of influential officials including congressmen, senators, and State Department directors.

My research indicates that there might have been more to the government’s sudden refusal than Alexander’s protest, though he believed himself to be fully to blame in jeopardizing the job and Neutra’s prestige. It was the early 1950s, and Elysian Park Heights, a large urban renewal and workforce housing project in Chavez Ravine, Los Angeles, was already underway. Suddenly the political ground shifted with the election of a new mayor in 1953 who wanted no part of public housing. The project’s demise was ensured when a leading Los Angeles housing official and proponent of the project refused to answer whether he was affiliated with groups being investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).[18] The project was painted with the red brush of socialism. Furthermore, with regard to the Karachi contract, one senator told Neutra in the summer 1954 that “There seems to be a question of [your] membership in the Hollywood chapter of the Arts, Sciences and Professions Council,” which was then being investigated by HUAC as part of the suspected “Communist infiltration of the Motion-Picture Industry, 1951 – 1952.”[19] Less than a month later, Alexander wrote the FBO giving permission to be investigated. After his own interview, Neutra wrote to Isaac White Carpenter, assistant secretary of state. “’As to my own loyalty to my country or testimony for it, I know there can be no doubt. I am more than glad to answer any question or stand any test so as to support with my best services our government in these perilous times,” he declared, suggesting that the “American rational approach to the design of buildings” was itself patriotic, a novel apologia I venture was never raised before or since.

By the end of March 1955 the contracts were finally signed. By early April, Neutra and his wife, Dione, were on a plane to Karachi.

Constructing the Embassy

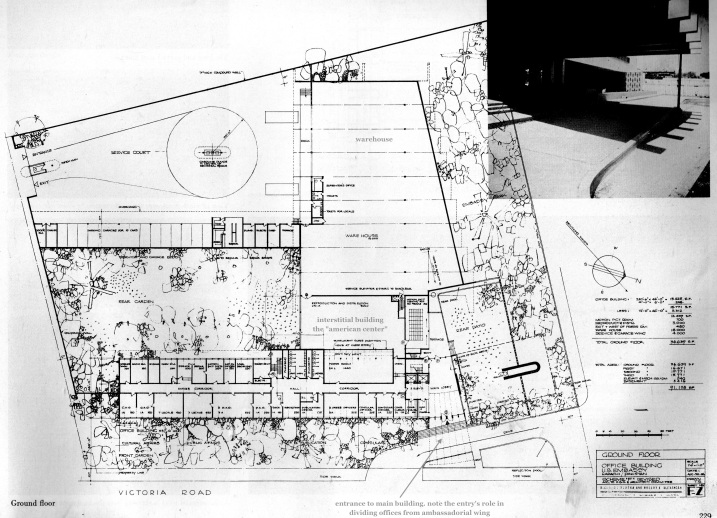

The lot is located in downtown Karachi in a prestigious area developed by the British in the 19th century. Now considered an economic hub, the area is populated today with government buildings, financial institutions, foreign consulates, and the famous Sind Club mentioned earlier. It is set back from Abdullah Haroon Road (Victoria Road) about 60 feet.

The primary building is a long four-story 90,000-square-foot box. It is asymmetrically divided into large and smaller wings, the smaller portion on the north angled a little to the west. The angle formed by that difference also defines the primary entry. Here, a vertical thrust of full-height glass panels and metal rises full-height. This main building is connected to a large one-story warehouse by an interstitial two-story building. This intermediary building, later known as The American Center, originally housed the cafeteria, reproductive services, and a small “motion picture room.” A secured service yard and covered garage bays occupies the southwest quadrant of the lot. The entire complex is markedly different from other downtown buildings by the broad lawns and extensive landscaping and hardscape features.

Embassy complex looking east. Warehouse on the right, main administration building on the left. Photo by ©Rondal Partridge and used with his family’s kind permission.

Largely designed between 1955 and 1956 in Los Angeles, actually getting the embassy constructed could be termed as torture to some and as an opportunity for cross-cultural collaboration to others. The primary and interstitial buildings of reinforced concrete reflect the engineering methodology standard for large-scale postwar buildings engineered in the U.S.: rational in character, the methodology had long absorbed the lessons of Henry Ford and 19th century efficiency expert Frederick Winslow Taylor. Parker, Zehnder and Associates was a well-respected and published engineering practice and the “go-to” firm for Neutra and Alexander; the engineers were simultaneously working on the firm’s much more daring steel design for the Cyclorama Building at the Gettysburg National Military Park, completed in 1962 and now in imminent danger of being demolished.[20]

In contrast, the Karachi warehouse was decidedly low-tech, with walls of an earthen-coloured concrete block with hollow clay tile infill used for the open arches. The concrete, both block and poured, tile, terrazzo were locally procured and mixed on site. As Annabel Jane Wharton remarked in Building the Cold War, “Making the Modern abroad was, after all, not so easy. Indeed, the effort required in the realization of a monumental Modernity where none had previously existed was nothing short of heroic. Basic building materials were difficult to obtain in Europe after World War II; they were completely lacking in the Middle East.”[21]

While researching Neutra’s landscape theories in a different archive, material from the 1930s, I found primary corroboration of the above in a slender folder in a corner cabinet; it was one of those moments where it’s the end of your research day, you are fairly satisfied. Your eye falls on something else and the world stops.

The folder contained a faded piece of smooth teletype paper, unknown today but doubtless from one of those kind of clattery machines in chaotic newsrooms one sees in old movies. To my astonishment, it was an undated, unbylined piece by a UPI reporter who told it like he saw it in Karachi, confirming what scholar Wharton stated and what Americans abroad knew first hand. Apparently never published, here is his exasperated report verbatim, including case changes for f/Fakir:

“The curse of a 19th century fakir [22]seems to have settled on the skeleton of a new American embassy being built here. According to a story widely accepted in Karachi, the Fakir cursed the embassy site years ago. He claimed the plot contained the tomb of a holy man and warned against construction of any kind. To illustrate his point, he toppled over dead. The property was then owned by a wealthy Parsi[23] merchant who ignored the fakir and went ahead with plans to build a mansion. The house later became known as “Sudden Death Lodge” after the merchant, his son, three workmen, and an English couple all died by accident or violence. The house was torn down in 1925 and the plot given over to a garbage dump until chosen as a site for the new American embassy. Construction began in Sept. 1957. To date, there has only been one death – that of an electrician. But the curse lingers on in more subtle ways. The new four-story embassy, designed by California’s RJN and REA [Richard J. Neutra and Robert E. Alexander], was scheduled for completion last March. Contractors now feel the building might be finished by late 1960. Others doubtfully mention a year later. [It was apparently completed in 1961.] Huge amounts of governmental red tape and an admirable desire to hold down U.S. dollar expenditures have helped the curse along. Although building cost estimates run 31.2 million, Washington has decreed only a tenth of that will be in dollars. The rest is to come from local currency accounts which the U.S. air programs have built up in foreign currencies. This has reduced a monumental procurement problem particularly with Pakistan lacking most of the equipment and building materials required to meet U.S. government specifications.”.

This is something Horace Hildreth, the ambassador to Pakistan 1953 – 1957, understood only too well — and six years earlier. Acknowledging that labor was being donated by the “Government of Pakistan,” in a 1955 letter to an FBO official Hildreth wrote,

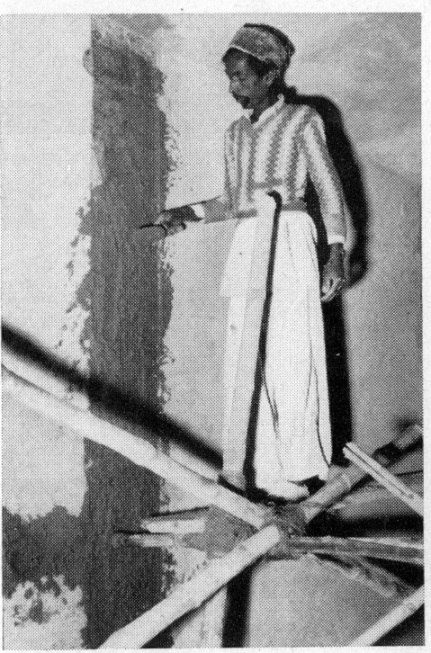

“The Embassy wishes to emphasize the difficulty of construction projects in Pakistan. The general prevailing inefficiency in the Government itself and in the fields of management and labor mean that an extraordinary degree of supervision will be necessary. We believe that it is imperative that an FBO-designated representative arrive in Karachi prior to the time construction is scheduled to begin and remain constantly on the spot.”His apprehensions were well founded. Five years later, construction underway at long last, co-architect Robert Alexander “complained loudly to the FBO that the concrete mix at Karachi was being watered down by the local contractor. He even warned of a possible building collapse (which fortunately never occurred), but he could do nothing to correct the problem because his firm had no contract to provide supervision and his complaints were dismissed.”[24]In one of his books, Neutra’s caption for a photograph of a Pakistani workman says it all. The photograph appears to be taken at night by flash, and portrays the workman apparently troweling a wall (troweling on point, an odd sight) that is uneven, typical of an initial “brown” coat of plaster, although it could also be a lack of craftsmanship, given the photo. Neutra enthusiastically writes, “The Asiatic workman must build a new architecture with the most primitive means …’ Dion Neutra, Richard’s middle son and project architect, noted in his new 2012 book on the legacy of the Neutras, The Neutras Then and Later that “We tried in every way to adapt the proposed construction method and schemes to what was the local practice … the planning was arduous and time-consuming.”

Neutra’s “Karachi workman.” Source: scan, Richard Neutra 1961 – 1966 Buildings and Projects. Photographer: attributed to Lucien Hervé.

In any case, the building represents the attempt of the State Department to insert and to some extent integrate an American construction paradigm into the local Pakistan building and craft culture.

The Building and Its Setting

In 1955, Neutra wrote a letter describing his ideas for the building to the distinguished Modern architect Pietro Belluschi. Belluschi was not only the dean of the School of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but more pertinent to any embassy project had just been appointed to the newly formed Architectural Advisory Committee (AAC), established in January 1954. The AAC, replete with architectural stars and American Institute of Architect Gold Medal winners and headed by a former Foreign Service officer, had been created in response to a growing Congressional alarm over the “so-called international” style of architecture used for important buildings abroad. In his letter, Neutra used a voice one would use only among confidantes and peers:

“The building is sited in the ‘green triangle of Karachi’ … where the bend in Victoria Road occurs between the entrances to the Sind Club garden and the Governor’s Palace, in the midst of the chlorophyll of foliage masses. We have added to the triangle the landscaped bay which reaches westward from the open space under the Ambassadorial wing and can be seen beyond the reflection pool. Water and foliage, greenery and shade, as here under the building, are rare in the desert of the southwest Pakistan coast … The scheme is a more clearly longitudinal one with a ‘locomotive’ pulling it toward the ‘triangle’ and a fortissimo enrichment of golden detail at the porte-cochere, projected far beyond the reflection pool, and above it the large green glare-proof glass of the “stack” of reception lobbies. On the north side, louvers [also gold-anodized], which I used early in the game [as early as 1947 with the Kaufmann Desert House.]”Rather disingenuously, given Alexander’s frustrations with the barrel vaults, Neutra tells Belluschi – who as a member of the AAC has some power over the design — that he was “inspired by the motif he saw elsewhere in south Asia with its rhythmically rolling one-story gables.” Then he gets more honest again: “There is practically no pleasant solution on the west front. All windows are a thermal nuisance and noo matter what we do the outlook is dismal. No embellishment of the yard will help – the sun will glare, and the best is to consider shaded narrow strips of openings here, in the direction of the Arabian Sea breezes. I wish the sea were close and visible …”

To be a little more specific, the “fortissimo enrichment” is the dramatic – if not downright gaudy – entrance. It comprised an elongated porte-cochere of seven large gold anodized aluminum beams with a thin metal roof, supported by seven steel cables aligned with the seven gold anodized aluminum vertical ribs dividing six full-height sections of glass windows.

U.S. Embassy, 2012. Photographed by Pakistani architect Arif Belgaumi, and used with permission. View looking southwest.

Neutra was not the only architect using gold-colored touches to highlight his embassy. Eero Saarinen’s design for the American Embassy, London, has plenty of gilded touches, included the massive gold anodized aluminum bald eagle adorning the cornice. Like the Karachi facility, that 1960 building, listed as a protected Grade II structure, has been sold. It is to be replaced by a new $1 billion embassy under construction. The new embassy, along the south bank of the River Thames near Battersea Park, will be surrounded by a green belt that in turn is will be be surrounded by a moat. Photo by Barbara Lamprecht, July 2012.

Behind the main building lies the entrance to the American Center (the small two-story building linking the warehouse and the main building). A short run of terrazzo steps leads down to the terrazzo patio and reflecting pool, where it joins a covered walkway leading to the warehouse area. Of note in this area is a signature Neutra trademark: this is an exterior light strip flush to a walkway ceiling and located at the far edge of the soffit. This asymmetric placement not only illuminated the path of travel, but also afforded a greater expanse of viewing radius at night for inhabitants inside a glass wall of a building. The gesture exemplifies Neutra’s concept of “biorealistic” architecture responding to ancient, primal human needs of “flight or fight.”

Both east and west elevations of the main building are characterized by a series of three continuous lengths of windows running the entire façade, the same windows Neutra rued in his letter to Belluschi. The windows are fronted by operable metal louvers with insect screens (Karachi is hot and humid.) The continuous strips of windows accentuate the structure’s strong horizontality and monumental presence.

Elevated one story, the executive/ambassadorial wing cantilevers northwest, supported by a long central pier aligned north south. A decorative one-story wall runs underneath the uplifted wing. The wall is perforated, a technique intended to respond to the long established Islamic/Arabic/Mogul architectural tradition of the mashrabiyah, a perforated wall that provides semi-privacy, animates a façade, and permits breezes. Many architects designing postwar embassies used such walls, and with greater abandon, such as the tour-de-force embassy in New Delhi, 1959, by Edward Durrell Stone; Baghdad, 1959, by Josep Lluis Sert; Manila, 1959, by Alfred Aydelott, and many others.[25]

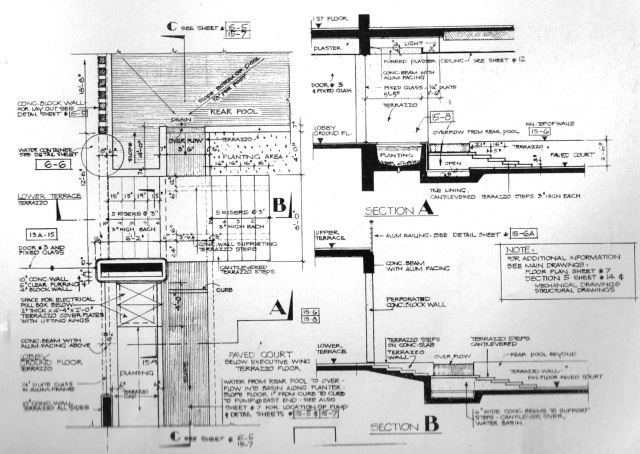

On the left is the plan view (a bird’s eye view) of the water channel leading from the reflecting pool; on the right you can see this in section (a view ‘cut through’.)

The Role of Water

Water is a continuous presence in the embassy in many identities: a broad, calm reflecting pool, a deeply incised channel, a waterfall, an ablution fountain, and a second pool at the property’s southeast prow. They all percolate through the complex, helping to unify the overall composition and mitigate, at least to some degree, a potential sense of disjointedness among the architectural pieces. They also introduce a refreshing microclimate and acoustical tempering—Neutra invariably required a detail to do double, or in this case triple, duty.

I’d like to discuss this intimacy with water a little more. Neutra had long included reflecting pools into his designs, either adjacent to a building, as he did for Rev. Robert Schuller’s Community Drive-In Church, Garden Grove, 1962;

A familiar image of Richard Neutra outside the rooftop penthouse at the VDL Research House II, designed by Dion and Richard Neutra, Los Angeles, 1966. Photography by Julius Shulman.

wandering in and out of a glass wall, as in the John Nesbitt House, Los Angeles, 1942, or the Constance Perkins House, Pasadena, 1955; or locating water on top of a house, he did for his own home, designed by Richard and Dion Neutra, Los Angeles, 1966.

The Constance Perkins House, Poppy Peak, Pasadena, 1953. Photograph by Raymond Richard Neutra and used with his permission.

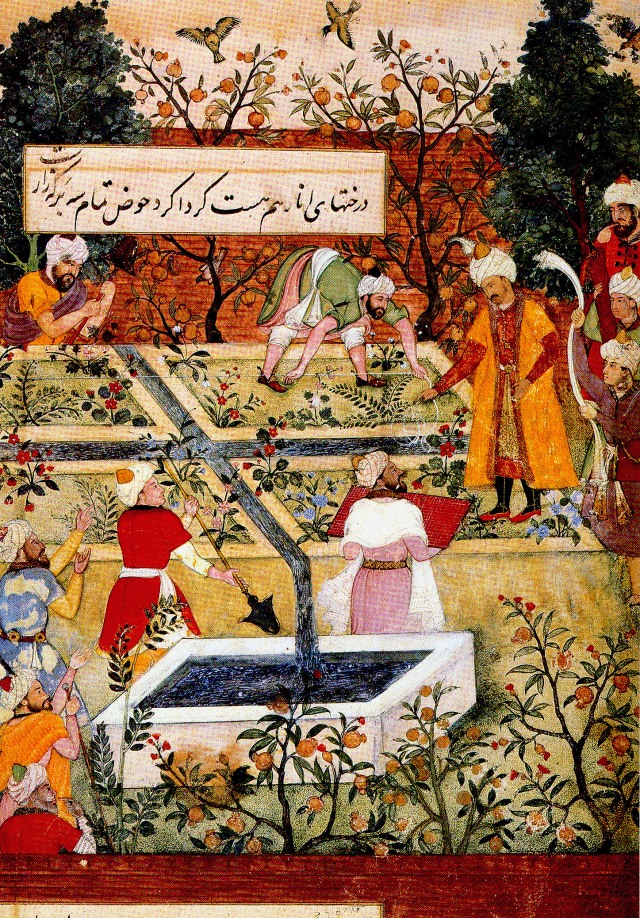

That said, the way he used water in Karachi, aligning a strip of landscaping with an identical width channel of water flanking the plantings, particularly resonated with a reverence for water in the dry Middle East. For example, deeply set water channels still nourish the roots of serried ranks of trees in gardens centuries old at Isfahan, Persia’s fabled garden city in central Iran. But in contrast to many Islamic/Arabic/Mogul gardens, which are often quite symmetrical, where Neutra located his channels and pools demonstrate the Modernist tenet of balanced asymmetry, or “dynamic symmetry.” He did this not because it was a stated tenet of the International Style as laid down by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock in 1932, but because he believed, based on his readings of human biology and cognitive systems, that such asymmetry was more natural that the “empty geometricity” of classical architecture (which he nonetheless admired.) In fact, he disliked the term “International Style” because its very name celebrated form-making at the expense of user needs. In contrast, through listening and probing he could then manipulate his refined kit of parts whose variables were client, site, culture, and budget. That is why Neutra and Alexander attended to Islamic ritual cleansing at Karachi, a sensitive gesture rarely seen in embassy design, a well-placed source told me. Neutra

“conceived of the outdoor area [below the cantilevered portion of the executive wing] as a prayer floor for the large number of Moslemic [stet] employees of the embassy, with an ablution pond and a fountain … Mr. Neutra felt it necessary to demonstrate visibly in his design the courtesy of his country to the staff of the Moslem faith and took it upon himself to discuss religious details with the Bar Mulvi, the highest church dignitary of West Pakistan.”[26]The tradition of open water channels cut deeply into the earth, called jubes, and centered fountains anchoring four cardinal jubes, called chahar bagh (chahar, four, and bagh, garden) is an ancient tradition in the Middle East and the subject of a vast literature. “Gudea, ruler of Lagash in Neo-Sumeria (c. 2100 BCE) said, ‘He who controls the rivers controls life’ … Water has always been the antithesis of desert and the necessary life-giver and the source of many gardens. Indeed, gardens cannot be conceived of without water.

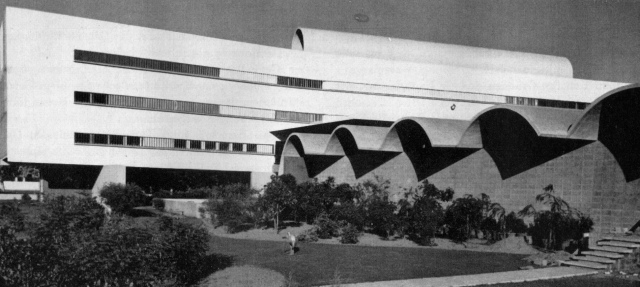

The Warehouse

Babur’s garden, Baburnama, 16th c. British Library. Source (and also the source for the quote on Gudea, is Electrummagazine’s superb essay on Persian Gardens at http://www.electrummagazine.com/2011/07/paradise-gardens-of-persia-eden-and-beyond-as-chahar-bagh/

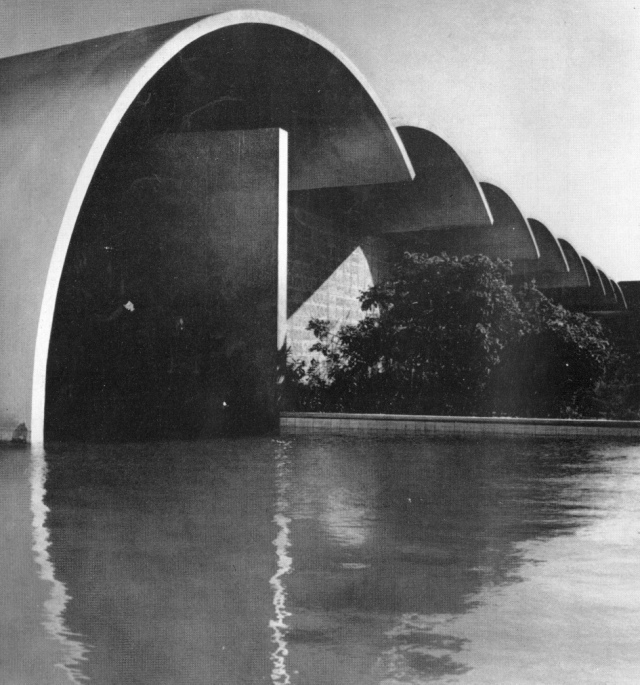

Nine thin-shell concrete barrel vaults roof the warehouse, and there is a good story connected to that as well. Alexander was not happy with the initial design: While visiting Karachi, he learned of

“ … the ready availability of cylindrical molds for casting concrete vault forms, and was determined to utilize such forms in an effort to counter what he believed to be Neutra’s overtly stark design of the main administration wing.”[27]

The moment of exquisite tension, where water, so historically precious in the Middle East, assumes a quiet hegemony as the element that unifies the composition. Photographer: Rondal Partridge, and used with the kind permission of his family.

The “interstitial” American Center in the middle; main administration (including the ‘Ambassadorial Wing’ on the left, warehouses on the right. Photo by ©Rondal Partridge and used with his family’s kind permission.

- … and a good look at “The American Center,” showing it acts as an interstitial construction between the main building and the warehouse. Not a great transition, to be sure. Photograph by Arif Belgaumi and used with permission.

The overall footprint of the warehouse responds to the site. Configured as a rectangle in plan, its rear wall is perpendicular to Abdullah Haroon Road. In contrast, and demonstrating how property lines can be harnessed for design, its angled northern wall is parallel to the north property line. Each vault steps back sequentially on the north moving from east to west.

The complex has been criticized for its disparate building components. I did too, before deciding I didn’t mind its abrupt transitions, but liked its frank expression of function and how thoughtfully it exploits its site. It is neither Neutra’s or Neutra and Alexander’s best work. It is, rather, a good mid-century building with plenty of life left. But there is one very fine moment here, at least to me, and that is where[28] the last, east-most barrel vault of the nine-arch warehouse enters the reflecting pool. It is a wonderfully ambivalent moment. American design using a Pakistani concrete building form enters that sacred element, water … but even more importantly, just as the vault pierces the water, the water assume a quite command in its role of unifying the entire complex … perhaps a good omen for the building’s future. (If the vault just hung above the water, rather than actually entering it, the effect would be much different, and weaker: any potential unity would be mildly suggested rather than implemented.) The photographs above illustrate how critical water is to the success of the site plan and how unity and fluidity are lost without it.

Given the careful hierarchy of plantings and his telltale drafting style when drawing landscaping on any plan, including this one, it is quite likely that Neutra himself designed the landscaped setting and gardens. No information on a landscape architect has come to light, and in any case Neutra was a master at landscape since his 1919 tutelage working with the famous Swiss botanist and landscape theorist Gustav Ammann. Tall, dark shrubs located in front of the warehouse opened out to an “American” lawn, a long swath of grass-like ground cover—even an embassy needs an American lawn!, for Neutra a stand-in for our evolutionary heritage and the sweep of the African savanna—in front of the warehouse labeled “Embassy Park.” The area was dotted with a few palm trees and mid-height plantings at the originally low perimeter wall on the north and a similar treatment was accorded for the primary elevation.

Understanding the Client: Neutra’s Other Projects in former West and East Pakistan

Neutra empirically observed all his life. Just as his “client interrogations” allowed him to inspect the individual, his never-ending international trips, commissions, lectures and appointments ensured that Neutra did not patronize local cultures but attempted to work with them. He employed a similar approach with regard to user needs and culture over 2,200 miles to the east, in Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan. One standard route from Karachi to Bangladesh, crossing all of India, includes Lahore, Pakistan, south of Islamabad, and the site of Neutra’s last project in Pakistan. Both were academic settings. In 1963, he was hired to design the university laboratories and library at the Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, in collaboration with Noon Qayum and Associates, Architects and Engineers. Although recent photographs suggest the library and other buildings may not have been built according to plan, perhaps because like the Embassy, construction administration was impossible, Neutra is credited for the library in plans at the University.[29] Other aspects of the large-scale project included departments in fishery, forestry, bee culture, silk weaving and pottery. Neutra’s January 1963 notes on the project indicate the range of his concerns in understanding his client; if ever an approach could be called a “character defining feature”—a phrase used in historic preservation to denote an important architectural element in a historic structure—understanding the client through what he called “client interrogations,” that included client-written narratives journaling daily activities from dawn to dusk would be Neutra’s “character defining feature. For example, Neutra’s notes include the Pakistani preference for a type of white rice; the daily caloric intake of the East Pakistan peasant (1,700, according to Neutra); and the need for the Pakistani rural community to stop using buffalo dung as fertilizer because of its negative long-range effects on the land, demonstrating his prescient thinking far exceeding the range of the immediate building.)

In Nature Near, Neutra described his experience in Bangladesh that speaks to his curiosity.

“As I usually do in such cases, whether I travel in Peru or Kenya, I began by sitting on the ground. I laid some color crayons beside me on the grass, put a big sketch pad on my knees, and proceeded to draw some scenes along the Brahmaputra, including the grinning inquisitive faces of the boys and girls who crowded around me. It is amazing what you can learn in such situations from facial expressions and spontaneous gestures.”Through such initial and then subsequent closer observation, Neutra threw out the foreboding fortress-like design he encountered and instead designed a campus that was more approachable to the rural poor it was supposed to help, surrounding it with huge water for water fowl, in a sense mimicking the watery rice fields. He designed a “distinctive domed silhouette” for the mosque. “I wanted [the peasants] to know that some real praying was done in these new precincts, and to hear the old muessin’s voice wafting out over the rice fields.”[30] As he had done in American schools, Neutra was also not above a bit of social re-engineering, arguing against separate schools for faculty and peasants and building a common school instead, which also conserved resources.

Neutra’s third and last project in Pakistan was the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, 1965-66, again with Noon Qyayum and Associates. In a draft letter in August 1965, he wrote a mission statement similar to FBO and OBO directives past and present: “The [Lahore] University should belong to the nation and be immediately recognizable as an Islamic institution, not as a foreign enclave. I have, therefore, suggested, that the mosque and the minaret symbolizing the spiritual link of this institution of learning to be visible and a very conspicuous symbol …” That sentiment notwithstanding, the schematic design sketches for this large-scale unbuilt project show an uninspired group of bland buildings made coherent by their planning, which in its partly open, partly closed building massing acts to both define the campus as one community and reach out to the rural community beyond. Neutra created a difficult brief for himself in wanting not to alienate the surrounding population (thus adding a gigantic mosque and minaret) while designing a Western, progressive, state-of-the-art technical institution.

In historic preservation parlance, a historic building has to communicate its “period of significance,” and usually historians begin investigating a potentially historic property by evaluating its integrity of design, materials, setting, etc. But significance of the Karachi Embassy, begins far below the exterior. Every member of its steel reinforced concrete frame was efficiently dimensioned by an American machine on an American factory floor and delivered by rail or ship to a port. The men who designed those steel girders, beams, columns, and struts were often American veterans who returned home to attend college and suck up an education under the newly revamped G.I. Bill.[31] Those steel members speak to the assumptions of prowess that reflected the wartime dedication and can-do, do-it-now discipline of those who said, as World War II veteran, the late architect Lyman Ennis said to me, “We just won a war, how hard could it be to build a house?” Likewise, the vertical thrust of clear glass rearing up in the middle of the Neutra and Alexander façade not only speaks to the industrialized 20th century technology of plate glass. The huge expanses of glass, so assured, so postwar self-confident, were literally and symbolically transparent. They embody the optimism of democracy. If that optimism feels incredible to us today, that same faith at least partly explains the cult of all things mid-century, home to Cary Grant’s charm and the lethal silkiness of Emma Peel as well as Modernism’s earnest pronouncements.

The Future

Touring the former Embassy. Note the concealed curved soffit for ambient ceiling washing of light. Photo by Arif Belgaumi. June 7, 2012.

Today that group of distinguished Pakistani citizens mentioned in the beginning are to be congratulated for preserving the embassy toward a new life and purpose. Step by step they developeded contacts with officials both in the U.S. State Department as well as the Pakistani officials overseeing listing the building. They recently toured the empty building, where much of the interior has been left untouched or can be rehabilitated. Led by Arif Belgaumi, who has been mounting a global campaign, the group includes: Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, Shahab Ghani, and Arshad Faruqui. Ms Chinoy is a documentary film maker and the founder of the Citizen Archive Project, one of the stakeholders in the proposal for the Neutra Cultural Center. Earlier this year she won an Oscar – Pakistan’s first – for a documentary of hers. Mr Ghani is the President of the Institute of Architects Pakistan (IAP) and has done a lot to garner support for the preservation of this building from various institutions like the AIA and the UIA. Mr Faruqui is Chairman of the Karachi Chapter of the IAP.

[2] Part of Abdullah Haroon Road is still called by its old name, Victoria Road, obviously a Raj name.

[3] See http://www.scnus.org/page.aspx?id=104659. “Target Hardening” is a term that military and Homeland Security people use for buildings to be less attractive targets.

[4] http://skepticalbureaucrat.blogspot.com/2011/01/obituary-for-consulate-office-building.html. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

[5] Ian Houseal, Contemporary Embassy Planning: Designing in an Age of Terror, Center for Global Initiatives, Carolina Papers on International Development, No. 15, Spring 2007.

[6] The Case Study House program was founded by critic and editor of arts + architecture John Entenza. The program existed from 1945 to 1966.

[7] See the work of Cliff May, master of the Ranch.

[8] Jane C. Loeffler, The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies, New York: Princeton Architectural Press/an Adst-Dacor Diplomats and Diplomacy Book, 45.

[9] arts and architecture, March 1953, 31.

[10] South Africa Architectural Record Vol 47, No 3-4, March April 1962.

[11] Architectural Record, May 1955, 187.

[12] Published posthumously, in German, written with his son Dion.

[13] Also published posthumously, in German, written with his son Dion.

[14] This was the Donald and Ann Brown House, 1968, in Rock Creek Park, and the story told to me by Ann Brown Sept. 24, 2001. during an interview .

[15] Many WWII veterans were educated at USC, the powerhouse for new ideas; postwar architects also got a leg up, i.e., world exposure, through John Entenza’s arts + architecture.

[16] Now slated for highly controversial demolition by the National Park Service.

[17] Loeffler, 49. See also Frank Mulcahy, Los Angeles Times, Nov. 23, 1958, “Buildings Show Design Influence of Southland.”

[18] This was Frank Wilkinson, whose passionate compassion for the people of Chavez Ravine, combined with his concern for urban conditions fostering disease and poverty, led him to fearlessly champion the project. It was my privilege to interview Mr. Wilkinson, a man still noble and active despite being in some sense broken by his indictment, before his death in 2006.

[19] I have not been able to yet confirm whether Neutra was a member of that Hollywood group, but it is true that he spoke to any group who would listen about the relationship of architecture to human well-being. While liberal, Neutra was largely apolitical, mostly leaving politics to his wife.

[20] Modern Steel Construction, American Institute of Steel Construction, Vol.8, No. 1, Jan. 1962, 3.

[21] Annabel Jane Wharton, Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2001, 7.

[22] Derived from the Arabic word for poverty, a fakir or faqir is a Muslim Sufi aesthetic or wandering religious mendicant monk or beggar.

[23] Parsi refers to a member of the larger of the two Zoroastrian communities in South Asia. Now declining in population, in the 1940s they were present in high numbers in the so-called “crown colonies” of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, reflecting long associations with the British Crown and the Raj.

[24] Loeffler, 145.

[25] See Loeffler, Figs. 71 – 109.

[26] South Africa Architectural Record, op.cit.

[27] Thomas S. Hines, Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, 245.

[28] I am aware that “moment” does not align with “where.”

[29] Email correspondence with Dr. Ken Breisch, president, Society of Architectural Historians, March 10, 2012. Ken and other SAH members toured the resource as part of a study tour.

[30] Neutra is misspelling muzzein, a man who calls the faithful to prayer.

[31] The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, signed June 22, also known as the G.I. Bill of Rights. It’s my belief that all the men, and few women, who went to college, many the first in their families, and studied architecture in fact changed the course of Modernism. A second clause of the bill, promoting zero-interest home loans for vets, fueled the intersection of innovative new postwar architecture and clients to buy it.

Comments

2 Responses to “The Obsolescence of Optimism? Neutra and Alexander’s U.S. Embassy, Karachi, Pakistan”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...-

[…] a world authority on Neutra, Barbara Lamprecht, puts it, “Neutra and Alexander’s effort was one of many embassy commissions, all reflecting […]

LikeLike

It has been my pleasure to assist the IAP in this effort. Congratulations on your success, and for the building’s long future.

LikeLike