The Languid Eros of the Lovell Health House

Written in 2014 … it’s 2025 and much has changed.

For Philip Johnson and Alfred Barr, reviewing entries for MOMA’s 1932 show on the International Style, Neutra’s Lovell Health House must have been a godsend. While every other building to be exhibited occupied relatively level ground, Neutra’s steel-framed house flew off the hillside into an LA canyon that is part Raymond Chandler country, part loose-limbed, insolent coyotes, and always Latino gardeners in battered trucks who know more than you ever will. It is both a place and a mindset that brittle East Coast critics, let alone the Europeans, don’t get, not really, and for sure didn’t get it in 1929 … and here was Neutra outdoing everyone. This “city Lovell” (not the “beach” Lovell) is less a bird, however, than an ocean liner sailing through a space, not water, very Corbu Vers, a point that can’t have escaped Barr/Johnson. The house is, perhaps, only momentarily tethered to a hill, shifting planes of white and dark, solid and void, exemplifying the asymmetry the MOMA boys were so keen on. (Neutra was too, but his asymmetry was based on biology, not on being politically correct.) “Cheap and thin,” Wright complained, disparaging Neutra to the curators, and if you think about it, “cheap” is not a bad thing to be, after all: we could all use a little more cheap … and “thin”—well, in earthquake country, thin and light might be rather a good idea, no? (Wasn’t proposing a one-story structure, framed in steel, glass, and wood—rather proposing a traditional multi-story pile of unreinforced masonry—the reason that the zealot Neutra won the commission for the addition to the Corona Bell School a year after the Long Beach Earthquake of 1933 that destroyed so many schools?)

That said, we all know Schindler’s design should have been included in the ’32 show. Of course, it’s concrete rather than steel, as it’s attempting to actually deal with sea and salt and corrosion. Steel windows would have rusted out. Perhaps it was not the wood, but Schindler’s patterned window mullions that they couldn’t stomach. Too Wrightian, too Josef Hoffmann.

I am far better equipped to write about the city house, and I have to say, bluntly, that I don’t “like” the Lovell Health House. I get why it’s important, that’s easy, and there are obviously obvious moments of glory, but there are other moments that are cognitively disturbing, i.e., the whole upper floor. You see, before my first visit to the Lovell, I spent time in many later or smaller Neutra houses, and could relax into Neutra’s sure-footed clarity of axes and his layers of orthogonal and diagonal lines of sight. I could delight in his lavish but shrewd gifts of “affordances” (providing so much personal choice in how one navigated space, protecting privacy as well as permitting free movement) in well daylighted spaces whose highly functional design was complex yet seemed to be so simple, so humble. There is none of that on the Lovell top floor, but rather zigs and zags. No clarity, no intention, of terminus. Yet: “Not a single thing displeases me,” Lovell loudly proclaimed to his Los Angeles Times audience.

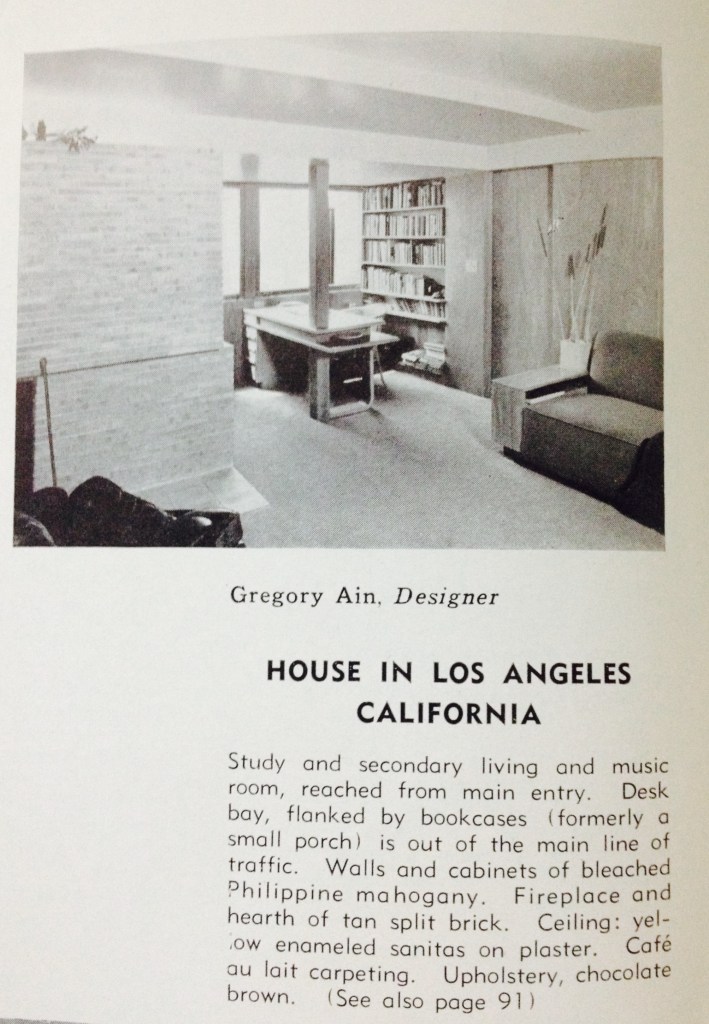

Um, not quite. Gregory Ain, Neutra’s super-talented, leftist protégé, reconfigured Lovell’s office for two reasons. Lovell’s desk originally faced south to the canyon view beyond the adjacent outdoor balcony. That placement also meant the desk, and its occupant, also faced away from the room’s east entrance, which was also the access to the rest of the upper floor. Not good defensive psychology. Worse, the desk and chair were located directly in a path of travel, so that anyone wanting access to areas beyond Lovell’s office had to walk directly behind Philip’s seated and generous back, and open a door directly adjacent to the desk. Ain (who did not like Neutra) recounts a very displeased diatribe, Lovell railing about Neutra, although it must be said that the awkward desk may have been added after Neutra’s work was done. In any case, note Ain’s clever solution. He harnesses part of that seldom-used balcony by tucking the office into a bay. Ain rotates the desk, so that Lovell could look up at both visitor— a classic defense strategy, and enjoy Nature now immediately to his right. His books are directly behind him within easy reach. Ain even exploits the requisite steel column so that it creates a subtle boundary for the doctor (and that provides a handy place for notes given a few magnets about.) Notably, in the plan Neutra included in a book published in 1951 (at least a decade after Ain’s remodel) Neutra shows neither desk nor chair, but rather his original balcony configuration, a graphic strategy that either blithely ignores the issue or shows that the desk was, improbably, an afterthought. And while impressed with the unrepentant formality of the master bathroom, I was taken aback because it was completely interior. Yes, of course there’s a big skylight, but it felt oddly claustrophobic. It was an Emperor’s Clothes moment, but who was I to call the Emperor naked?

Then there is the whole problem of no overhangs on the southwest corner: you simply cannot live in LA without understanding the implications of a southwest exposure with single-pane glass. What could Neutra have been thinking?

Fortunately, the Viennese native learned to adapt. And in any case, to dwell on the rabbit warren of the upper floor or the lack of attention to human comfort is foolish. Rather, the important trajectory is walking across the “gangplank” from Dundee Drive, leaving the earth for the air, enjoying the porthole windows and curved railings that set the jaunty nautical, perhaps ModernE tone. The door swings open and just to your left, the famous glass-enclosed double-height staircase with the embedded Model A headlight flows down in majesty. (Neutra protégé Gregory Ain personally contributed the homage to Henry Ford from his own car, legend has it, though he probably grumbled about it).

This grand entrée leads to a kind of reverse piano nobile that is an elongated living space both kinetic and serene. Here is self-confidence. Neutra’s famous long suspended light trough weaves shifting ceiling and floor heights together, easily putting paid to Bachelard’s requisites for cave and attic. One might miss the subtle wall-washing of the coved upper walls in the dining area on the west. In fact, from when you pad about by dawn or flash a leg at a midnight fete, the lighting Neutra offers to complement the sun is nothing short of extraordinary.

There are nuances everywhere, subtle curves tempering right angles, textures of grey cloth, light decanted by silver and dark blue-grey, ebony, cream, white, black, and the blonde-gold of the fireplace stone. There are the low datum lines defined by the horizontal window mullions that are echoed in the low lines of the furniture and built-ins. If you listen, your ear cocked like that famous picture of a deaf Adolf Loos with that elephant of a hearing aid, a languid eros waits for you.

But the space that haunts me is neither the wandering incoherent spaces of the upper rabbit warren or the flowing spatial transitions of the middle piano nobile. Below these floors is the pool adjacent to the kind of room we architect-types love: semi-industrial, an anonymous high-ceilinged box, half-buried into the hill, concrete floor, lots of big steel-framed windows … this is where Lovell kept his exercise equipment and where Leah Lovell and Pauline Schindler taught their progressive school lessons. Perhaps we have built up a sweat and are ready for the cool shock of

water. Half of the pool is under the house, a dark and shaded space. The other half reaches into the open air of the canyon, open to the sky. As we know, Philip Lovell endlessly preached nude bathing, and yet the pool here, thank God, conjures no images of his stolid-solid body, but rather of some androgynous naked body, perhaps your body, my body, not sure, doesn’t matter, in any case swimming into the sun, out into the freedom of the canyon, flipping, and then returning to the bowels of the hill, the bowels of the building. Back and forth, in and out, this silent rhythm, from darkness into the sunshine, sunshine into darkness, is so very LA to me, as well as so much the essence of the ontological human condition. The idea of rhythm easily translates to architecture, just look at the rhythm of the windows above. The steady, even spacing, of pairs of steel casement windows, exactly 3’- 3-1/2” wide not exactly an American residential construction norm. So below the house, below the rabbit warren of the top floor and the majestic Staats Oper Viennese promenade of Alberti’s man, Inigo Jones’s piano nobile, here is the naked, fragile, strong body, swimming, back and forth, coming out of the pool, shaking water off the skin, toweling off, and mounting the exterior stairs to assume the civitas of modernity waiting upstairs.

Thus far the discussion has been about vertically sectioning the house. Upper, middle, lower. The Lovell can also be cut down the middle, like a knife, east to west, to reveal the Lovell’s inherent theatre. The division between server and the served is no “upstairs downstairs” but north and south. The southern part of the house, where the living area and grand staircase abide, is divided by a long wall from the north that houses the kitchen, maid’s quarters, and supporting spaces. [Eleven years later, this sentence would be changed to reflect that some of the “supporting” spaces were for the Lovell’s young boys, and lovely bedrooms they were … and are again.]

But what a kitchen! This long, high-ceilinged space is very 1920s style Modern, but somehow feels like a farmhouse kitchen. Take typical upper cabinets. Neutra nudges the uppers up a bit, then provides a secondary, smaller bank of cabinets that are recessed below the projecting upper cabinets. [Whoops, wrong again, not Neutra but later. Still, odd that the Jardinette Apartments, completed a year earlier, had the very same condition.] This little recessed bank has sliding walls, providing more ways to exploit storage and aesthetically layering spatial transitions throughout the room. On the east end of the kitchen a pony wall book case separates work areas nfrom a banquette of table and built-in benches. In the corner, behind a door, the interior painted a brilliant Chinese red, is the famous tall ant-defying revolving vegetable cooler Neutra was so proud of (I know: you are dying to know how ants were defied. So. Little canisters of oil top and bottom of the pole prevent the ant army from proceeding to your fruit and veg. Neutra did it elsewhere a million times, usually even venting it outdoors, so there was always fresh air washing the vegetables.) And the color! … a dusty, dusky yellow throughout quiets the kitchen air, a great contrast to the taut silver thoroughbred of a space just beyond the swinging door, out on stage. In the dusky yellow kitchen, there is serenity, good temper, coloring books, and the smell of baking.

Below you, today, the pool is empty and dry. It is cracked and broken. But 90 years ago a naked body swims back and forth, in and out, light and dark, Apollo and Dionysus, ego and id, with each stroke the arm reaches out into the dangerous free-fall above the scrub of the canyon. Reaches the edge, flips, and heads back to into the groin of the earth. The body is the ultimate metronome. Welcome to Los Angeles.

Very fascinating Barbara. You may not Know that Edward Weston’s son Neil was Ain’s carpenter on the job and he also hung Weston portraits of the Lovell boys.

LikeLike